Comics played a large role during my childhood. In the late eighties, I used to look forward to the newest issues of Indrajal Comics. They published stories featuring many superheroes, but the two main characters featured were my childhood heroes Phantom and Mandrake. When Indrajal Comics was in circulation, I used to read them often, but I wasn’t fanatical about them. Then after they went out of publication in 1989, I went through phases of disinterest, to inquisitiveness, to obsessively searching for the books. It was a quest, almost like a pilgrimage to amass all Indrajal Comics strips ever published. Once I’ve nearly finished that, I learned that Hermes Press is going to reprint all Golden era comics of Phantom. A few years later, Titan Comics decided to bring out the other character created by the prolific Lee Falk — Mandrake the magician. The stories I grew up reading were reprints of many later issues, but it was through those stories that I formed an idea about the central characters. Going back where their journeys first started, these reprints of early years’ issues had taught me new things that would not have been very apparent thirty years back.

Phantom’s Belt, First Indrajal Comics in India

Lal Jadukarir rahasya, first Indrajal comics in Bengali

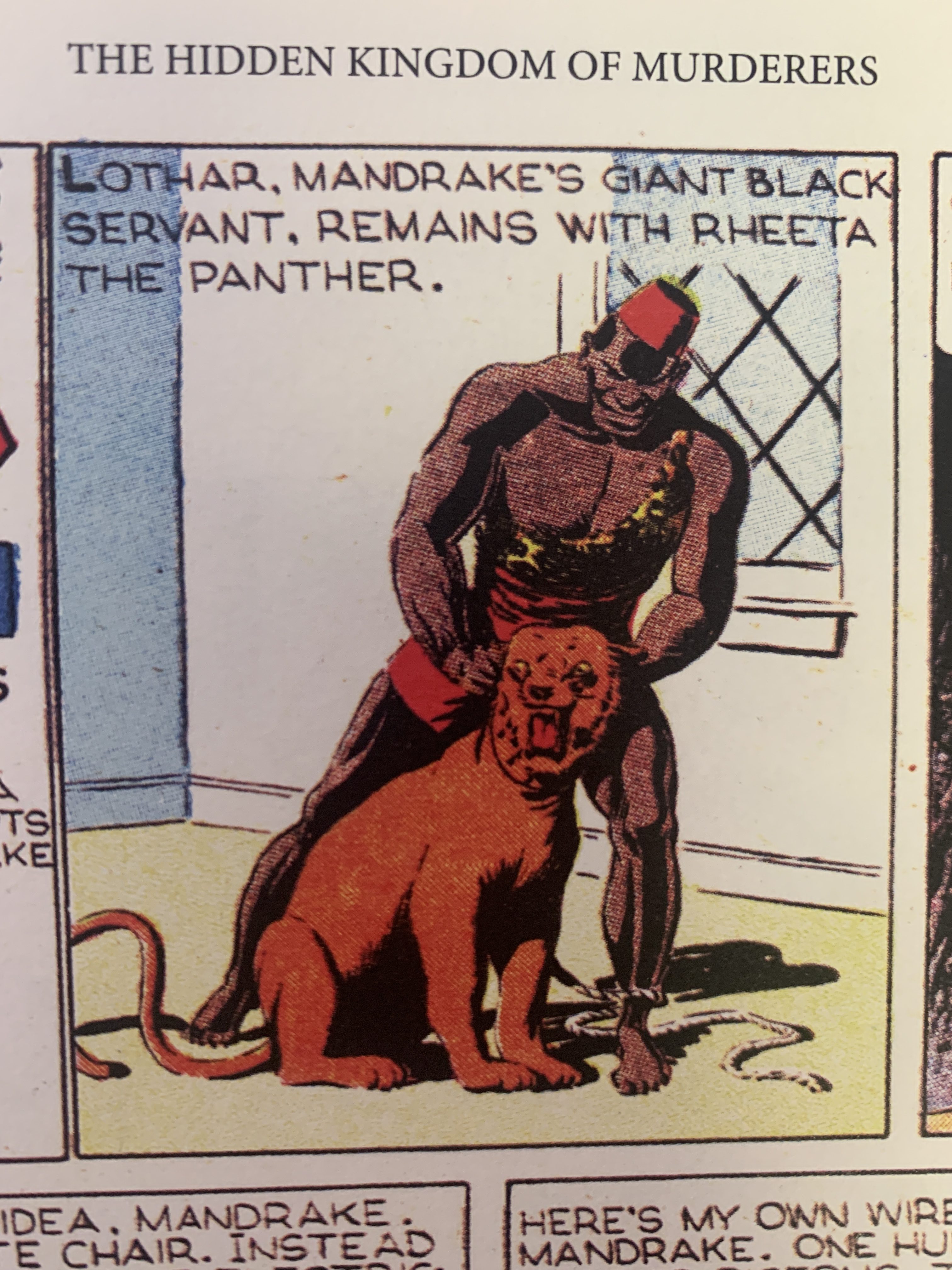

Reading 1930’s Mandrake is almost a throwback to the society and its expectations of that epoch. That’s why, in the very first Mandrake adventure, we are introduced to Lothar as Mandrake’s “Giant black servant”. He is black, wears a leopard skin or skin printed fabric, calls Mandrake “Master” and speaks broken incoherent English. It was written in the description that Mandrake’s “black slave” Lothar does this or that. Thirty years back, the Lothar I was introduced to, was Mandrake’s friend, like equals, spoke many languages, was a black belt. And he is more brown and less black. He called Mandrake “Mandrake”, not “Master”. The image of Lothar was perhaps how he was perceived in post-depression America — the black slave of the magnificent Mandrake. The Lothar I grew up with is the 1960’s version, on the other hand, is around the Civil Rights Movement and had undergone a major change of character. It just echoed an image of how society started to perceive non-whites as equals. Likewise, when we think about the character of Hojo, the Japanese chef who speaks many languages and heads the Inter-intel, you cannot imagine him being featured in the 1930s. In the 60s comics, the societal lenience on race and colour were reflected in the contemporary comics like Mandrake and Phantom.

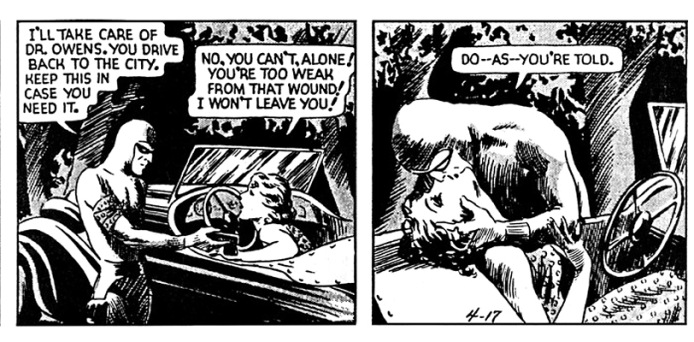

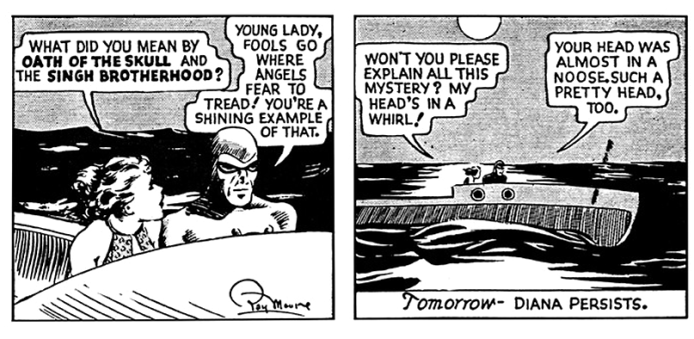

A similar shift is noticed in how women were presented in these stories as well. The 1930s versions used terms to describe women we now can’t even think about. The comics were positively sexist, but only branding the artist who created them as sexist would be almost anachronistic. Lee Falk was a common man with extraordinary skills in creating comics. His ideas about women reflected the perception of women in society. They were shown to be fragile, dominated by male characters. Emmeline Pankhurst and Amelia Earhart hadn’t made a substantial change in people’s perspective towards women. On the other hand, the 1960s editions show much more parity in the depiction of women in the comics. They are far more independent, strong and outspoken. In fact, many of the comics around the 1960s started showing women as villains because perhaps there was still no willingness to show a female character as good as the male protagonist, but by showing them on the wrong side, it was inevitable that they will be defeated at the end. Nevertheless, the depiction of female characters in Phantom and Mandrake comics has gone through a major overhaul and the comics published characters whose only role in the story wasn’t about being the weakling in the adventure and throw herself on the central character every now and often. In some cases, the efforts of featuring women, especially the partners of the central protagonist were so intense that at times their qualities appeared as exaggerated as the superpowers of the male characters. They had to be super rich, speak several languages, hold a role of UN ambassador, know martial arts, related to nobility — in short, it cannot be a common woman to be associated with an extraordinary superhero. Indirectly the new generation authors sustained the patriarchy. However, that is a different argument. At least, women were no longer seen as merely a pretty face.

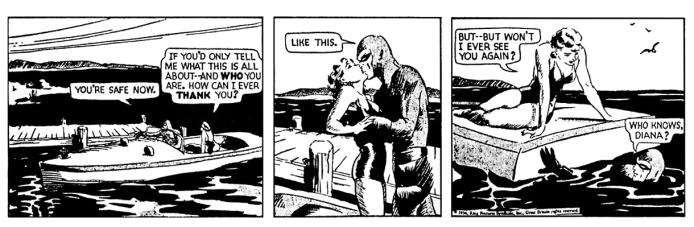

So, when we turn the pages of the first phantom book from Hermes press, where Diana Palmer asks who he was after he saved her and how could she thank him, Phantom just kissed her and said “Like this” and dives back in the sea. The next time they see each other, Phantom is aware that Diana is going out with someone, yet he kisses her while saying goodbye. The word consent probably didn’t exist then in that context. Men could choose their woman and taunt, tease, grab or kiss them, or worse. I guess much hasn’t changed now, but at least we pretend to be more civil now and push issues like this under the carpet. Comics is not an exception. The patriarchy that was blatant in those early years, they became subtler, but never eliminated. That’s why, the first son always becomes the next Phantom, not the first child. I think Frew or the Danish version of Phantom has only just thought about making Heloise the 22nd Phantom rather than Kit.

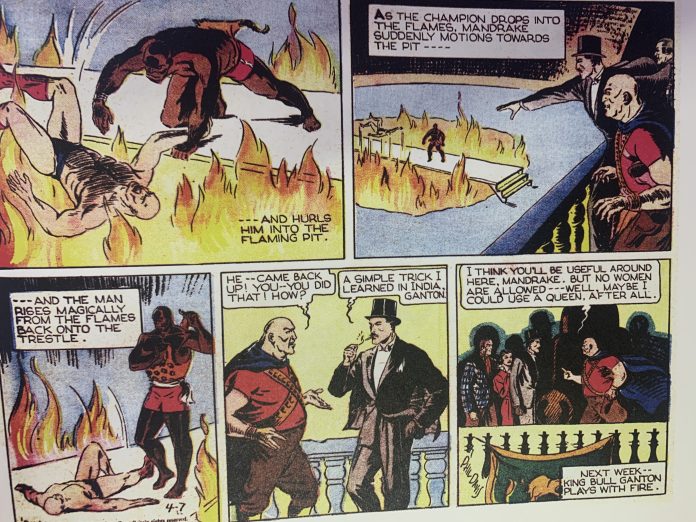

The storyline during the 60’s comics was also made more informative and less fantastic. The 1930’s Mandrake wasn’t just a magician with phenomenal hypnotising powers, but he used to do magic as well. In one of the first episodes, Mandrake transforms one of his aides into a leopard. On another, he lifted a man froom falling into a fire-pit. He could make things happen rather than just pretending to, like the later stories, more like a Harry Potter than David Blaine. In my view, with changing times, the readers became savvier about science and reality. Whilst Superman continued flying around and melting every obstacle with his X-ray vision, Mandrake became more humane. He became a hypnotist and helped the authorities to fight crime. Likewise, in the later issues, Phantom did not control the thousands of miles between the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean. He becomes the chief of jungle patrol, the security force that keeps peace in the jungle. It’s no longer down to Phantom to tackle all the miscreants. Although the introduction of Stegy the stegosaurus and Hzz & Hrz cave monsters in phantom stories wasn’t a shining example, on a broader scale, the characters were more down to earth.

During 1930s America, racism was rife, a non-white principal character was unimaginable, and women in comics were merely a pretty face – used to fill up a few tiles and to prove the bravery of the comics heroes. In the 1960s, all social divisions were still there, yet the difference was remarkable. These changes in the society are clearly visible in the Mandrake and Phantom comics of the two eras. As study subject, Phantom may be even more interesting, since not all stories were reprints of the American versions. Team Fantomen, for example, was an entirely different set of stories, written and illustrated by Scandinavian artists. The stories of Team Fantomen may present a different outlook to life, possibly a reflection of the Scandinavian society of the epoch, especially since they have been in circulation for over 60 years.

As children, we saw comics as the world we would like to grow up into and have an idol. As grown-ups, we become a part of the period we are living in, adhering to its societal norms. We learn that heroes have their follies, etched into their persona but their creators. It would have been interesting, if Lee Falk was still illustrating, to see how he would have represented the society and relationships during the 21st century. Will the 22nd Phantom marry someone or will he have a partner? Will there be a female Phantom? Will Mandrake and Narda argue over silly things? Will there be LGBTQI characters? Will they feature interracial couples? Will there be a Phantom who doesn’t like to be Phantom but do it because he/she’s expected to? And going forward, how will the stories shape up in future? These are compelling questions for which we have no answers. Perhaps I’ll leave the task to my children to dissect the stories of 2030 and compare them with 1930 versions. I hope that I’ll live to watch their appalled expression reading that Mandrake had a giant black slave, or Phantom forcing a kiss on Diana. I hope turning the pages of the comic books of the 1930s and 1960s will make them appreciate how far society will have been progressed in a century. And how we are in the need of superheroes, because humans, despite having come a long way on the vices prevalent in the 20th century, have created new evils. Perhaps the Mandrake and Phantom of tomorrow will feature the inequality, terrorism, post-truth politics, environmental catastrophe, the middle-east, religious persecution. Perhaps they never will, if the artist is not bold enough to rise above the societal mediocrity, like Lee Falk in 1930.